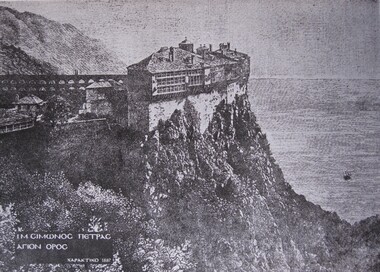

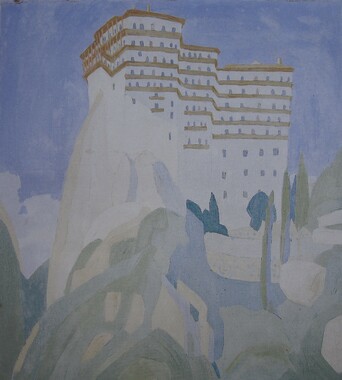

Historical Background of Simonopetra. The Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra is located on the southwest side of Mount Athos and its complex, an area of 7,000 square metres total, is built on a granite rock, about 300 metres from the surface of the sea. Simonopetra unfolds in seven floors with several balconies – a unique monument of Byzantine and post-Byzantine architecture.

The Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra is located on the southwest side of Mount Athos and its complex, an area of 7,000 square metres total, is built on a granite rock, about 300 metres from the surface of the sea. Simonopetra unfolds in seven floors with several balconies – a unique monument of Byzantine and post-Byzantine architecture.

Its history dates from the 13th century, the period during which Saint Simon the Myroblyte lived (his date of birth is unknown; he died on December 28, 1257). After a vision that he experienced while practising in a cave in the wider area, Simon decided to establish a monastery in honour of the birth of Christ, giving it the name New Bethlehem. However, after his death the nickname Simonos Petra (Simon’s Rock) or Simonopetra prevailed.

Between 1365 and 1371, the Monastery entered a new phase of operation and development, when its second owner, the Serbian Jovan Uglješa (the despot of Serres at the time), proceeded to renovate and expand it, providing rich donations and strengthening it with metochia and relics.

Major landmarks of the Monastery’s history include three large fires that destroyed buildings and a treasure trove of relics, and cost the lives of many of its monks. The first fire broke out in 1580 after lightning struck the Monastery, causing great damage to its facilities and cells and burning valuable assets (relics, vestments, codices, sigils, etc.). The fact that the monks were forced to leave Simonopetra and settle at Xenophontos Monastery is a testament to the extent of the catastrophe. However, following the actions of the monastery’s abbot, Eugene, who travelled to the Danubian Principalities to raise funds, the ruler of Wallachia, Michael the Brave (1558-1601) undertook the costs of its reconstruction.

causing great damage to its facilities and cells and burning valuable assets (relics, vestments, codices, sigils, etc.). The fact that the monks were forced to leave Simonopetra and settle at Xenophontos Monastery is a testament to the extent of the catastrophe. However, following the actions of the monastery’s abbot, Eugene, who travelled to the Danubian Principalities to raise funds, the ruler of Wallachia, Michael the Brave (1558-1601) undertook the costs of its reconstruction.

The second fire, in 1622, combined with the heavy taxation imposed by the Turks, led the Monastery to decline and desolation. Thanks to the efforts of the hieromonk Ioasaph of Mytilene, Simonopetra reopened at the end of the 18th century. It was at that time that the multi-storey building on the south side was constructed. In 1821, during the Greek Revolution, the monastery was deserted for five years, but was rebuilt by the hieromonk and later abbot of Simonopetra Ambrosius, while in 1864, during the abbotship of Neophytos (1828-1907), the south wing was erected.

In 1891 the Monastery was to be hit by a new catastrophic fire, which completely destroyed its eastern side; neither the Katholikon nor the Library escaped the flames. In addition, the buildings that housed the altar, the guest house, the abbot’s quarters, four chapels, the hospital, and the monks’ cells were destroyed. At least the coffer with all the heirlooms, documents, holy relics and vestments was saved.

which completely destroyed its eastern side; neither the Katholikon nor the Library escaped the flames. In addition, the buildings that housed the altar, the guest house, the abbot’s quarters, four chapels, the hospital, and the monks’ cells were destroyed. At least the coffer with all the heirlooms, documents, holy relics and vestments was saved.

News of the destruction of Simonopetra reached its abbot, Neophytos, in Russia, where he had been since October 1888, accompanied by the monk Dionysios and the deacon and subsequent abbot Ioannikios, in order to raise financial aid for the Monastery. Upon returning to Mount Athos in 1892, Neophytos found the Monastery in such a tragic state that he thought of building a new monastery at a more even location.  This idea was soon abandoned and the work for the restoration of the Monastery began immediately. Instead of renovating the now damaged east side, Neophytos decided to build a new multi-storey wing next to it. Work on the construction of the “St. Mary Magdalene” wing, as it was named in honour of the Monastery’s patron saint, began in 1897 and was completed in 1902.

This idea was soon abandoned and the work for the restoration of the Monastery began immediately. Instead of renovating the now damaged east side, Neophytos decided to build a new multi-storey wing next to it. Work on the construction of the “St. Mary Magdalene” wing, as it was named in honour of the Monastery’s patron saint, began in 1897 and was completed in 1902.

With Ioannikios serving as its abbot from 1907, Simonopetra entered a new phase of prosperity, in conjunction with the liberation of Mount Athos from Ottoman rule in 1912. The sudden death of Ioannikios in 1919, at the age of just 52, did not hinder the development of the Monastery; on the contrary, his successor Ieronymos (1871-1956) carried on his important work. The years of the Occupation were difficult, with the shortage of staff adding even more strain and the risk of the Monastery becoming derelict lurking throughout the next two decades, until 1973.

At that time, a new twenty-member brotherhood from Meteora settled at the Monastery headed by the elder Emilianos (1934-2019) who was also elected its prior. Until 1995, as long as his health allowed, Emilianos attached great importance to the inner life of the Monastery, combining the experience of the older monks with the enthusiasm of the younger ones and attracting new monks to join the brotherhood. The Archimandrite Eliseus of Simonopetra has served as the Monastery’s abbot since 2000.

headed by the elder Emilianos (1934-2019) who was also elected its prior. Until 1995, as long as his health allowed, Emilianos attached great importance to the inner life of the Monastery, combining the experience of the older monks with the enthusiasm of the younger ones and attracting new monks to join the brotherhood. The Archimandrite Eliseus of Simonopetra has served as the Monastery’s abbot since 2000.

Monastery Administration of Simonopetra. The Holy Monastery of Simonopetra has followed a communal way of life and administration since 1801. It is currently the residence of 65 monks. The Monastery’s Representation and annex buildings, housing its services and cells, are located in Karyes — the capital of Mount Athos. The Monastery is also in possession of six seats and several metochia in the Greek mainland and islands, as well as three metochia in areas of France.

Library of Simonos Petra – The Manuscripts. The history of the Library of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra is divided into two time periods, the period before the fire of May 28, 1891 and the period after. As mentioned, the great fire that started from the Monastery’s bakery burned down the area where the Library was housed, as well as all its printed and manuscript books, resulting in the Library being rebuilt from scratch.

However, based on the list of manuscript codices compiled by the professor of the University of Athens Spyridon Lambros in 1880, we learn that until 1891 the Monastery held at least 245 manuscripts (56 of which were musical), dating from the 9th to the 19th century. The oldest of these documents was a study on the Gospel of John, written by John Chrysostom on parchment during the 9th century, while the oldest dated document was a gospel copied by the priest Constantine in 1189.

until 1891 the Monastery held at least 245 manuscripts (56 of which were musical), dating from the 9th to the 19th century. The oldest of these documents was a study on the Gospel of John, written by John Chrysostom on parchment during the 9th century, while the oldest dated document was a gospel copied by the priest Constantine in 1189.

According to the historian Kriton Chryssochoidis, the establishment of the Library of Manuscripts at the Simonopetra Monastery began with its foundation and continued in the following years with donations, purchases and copies of codices.

The first known donation came from the Serbian despot Jovan Uglješa (1365-1371), while at the beginning of the 16th century the bishop and abbot of the Monastery, Gerasimos, donated 54 manuscript codices. From the middle of the 16th century and throughout the 17th, the Library was enriched with codices, most of which were manuscripts of ascetic and hagiological texts, copied by the monks of Simonopetra. These books eventually amounted to 103 manuscripts, i.e. 55% of the total collection, as mentioned by K. Chryssochoidis. It should be noted that the copying of liturgical books was a common practice in all the monasteries of Mount Athos and, despite the discovery of printing in the middle of the 15th century, the copying and use of manuscripts continued. The continuation of this practice is mainly attributed to the high cost of printed books, but there was another factor, less practical, that enhanced the production and acquisition of manuscripts. Specifically, each manuscript copy came with additional aesthetic value and fidelity exclusive to it alone, products of the copier’s toil.

while at the beginning of the 16th century the bishop and abbot of the Monastery, Gerasimos, donated 54 manuscript codices. From the middle of the 16th century and throughout the 17th, the Library was enriched with codices, most of which were manuscripts of ascetic and hagiological texts, copied by the monks of Simonopetra. These books eventually amounted to 103 manuscripts, i.e. 55% of the total collection, as mentioned by K. Chryssochoidis. It should be noted that the copying of liturgical books was a common practice in all the monasteries of Mount Athos and, despite the discovery of printing in the middle of the 15th century, the copying and use of manuscripts continued. The continuation of this practice is mainly attributed to the high cost of printed books, but there was another factor, less practical, that enhanced the production and acquisition of manuscripts. Specifically, each manuscript copy came with additional aesthetic value and fidelity exclusive to it alone, products of the copier’s toil.

After the fire of 1891, the new library of manuscripts was constructed, as befitted the predominance of the printed book at the time, with the objective of housing documents of museum value rather than those intended for immediate use. This pursuit arose from the general need for the monasteries of Mount Athos to include among their collections a category of relics, which would also feature valuable manuscripts.

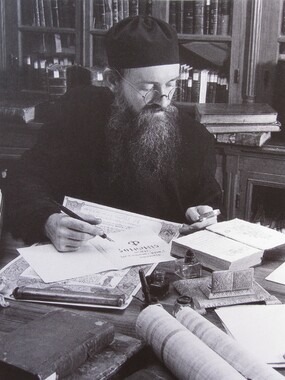

The monastery’s modern-day collection, according to philologist and palaeographer Panagiotis Sotiroudis, who began cataloguing the monastery’s manuscripts in 2007 (the catalogue was published in 2012), consists of 179 manuscripts, all in paper except for one parchment saved in its entirety and a few surviving fragments from others. Chronologically, only four date back to the 12th (1), 14th (1) and 16th (2) centuries, while the rest – with the exception of the aforementioned parchment fragments – date from periods between the 17th and 20th centuries.  The content of the manuscripts concerns mainly theological, ecclesiastical and musical subject matter, with an emphasis on the services of the saints, especially for the patrons of the Monastery, Simon the Myroblyte and Mary Magdalene, but also other saints whose remains are kept there. The other manuscript books kept in the collection are classified into categories: legal-canonical, medical, school textbooks, books on rhetoric, grammar books, guides on lexicography, mathimataria, chronologies, et al.

The content of the manuscripts concerns mainly theological, ecclesiastical and musical subject matter, with an emphasis on the services of the saints, especially for the patrons of the Monastery, Simon the Myroblyte and Mary Magdalene, but also other saints whose remains are kept there. The other manuscript books kept in the collection are classified into categories: legal-canonical, medical, school textbooks, books on rhetoric, grammar books, guides on lexicography, mathimataria, chronologies, et al.

Library of Simonos Petra – Printed Works. Until 1891, in addition to the manuscripts, Simonopetra had a collection of printed books, which were also burned by the flames of the fire. According to the Κατάλογος των εν τη πυρκαϊά 1891 πυρπολυθέντων κυριοτέρων πραγμάτων [Catalogue of the main items burned in the fire of 1891], compiled in the wake of the catastrophe between 1891 and 1893, at least 750 volumes of printed books were destroyed, in addition to the 245 manuscripts. In fact, as evidenced by other data from the Monastery’s Archive, the actual number was much higher. Simonopetra had a remarkable Library that was located above the narthex of the Katholikon and where books from many fields (e.g. works by ancient Greek authors, works of ancient and Byzantine history, dictionaries, guides to Greek and French grammar and syntax, books on arithmetic and geography, physics, medicine, et al.) were kept in addition to the liturgical books for the daily needs of the Monastery. It also boasted a remarkable collection of periodicals, including Εκκλησιαστική Αλήθεια [Ecclesiastical Truth], Ανατολικός Αστέρας [Eastern Star], Θράκη [Thrace], Φάρος της Μακεδονίας [Macedonia Beacon], Ελικωνιάδες Μούσες [Muses of Helicon], et al.

that was located above the narthex of the Katholikon and where books from many fields (e.g. works by ancient Greek authors, works of ancient and Byzantine history, dictionaries, guides to Greek and French grammar and syntax, books on arithmetic and geography, physics, medicine, et al.) were kept in addition to the liturgical books for the daily needs of the Monastery. It also boasted a remarkable collection of periodicals, including Εκκλησιαστική Αλήθεια [Ecclesiastical Truth], Ανατολικός Αστέρας [Eastern Star], Θράκη [Thrace], Φάρος της Μακεδονίας [Macedonia Beacon], Ελικωνιάδες Μούσες [Muses of Helicon], et al.

The reconstruction and enrichment of the Library after 1891 was a key priority for the monks, as evidenced by the amounts spent for this purpose during the first five years after the fire: 773 groschen in 1892, 796 in 1893, 902 in 1894, while in 1895 expenditures skyrocketed to 4,984 groschen and were reduced to 2,345 in 1896, to finally stabilise at 400 groschen a year thereafter. Another source of acquisitions were the donations from individuals and institutions to the Library at the beginning of the 20th century. Donations from Eleni Evgeniou Palli, the widow of Andreas Mamoukas, the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, Konstantinos Doukakis, and others stand out.

In 1909 the librarian Nilos of Simonopetra attempted a first recording of the printed books kept at the Monastery, estimating their number at 252. Of these, 149 survive to this day, 39 (all liturgical) are missing, while another 43 were impossible to identify.

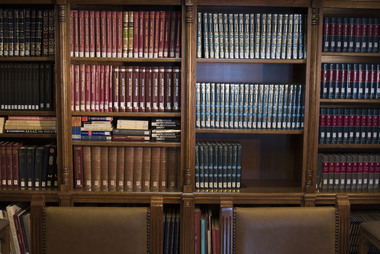

Today the Library of Simonopetra, which is now located on the 7th floor of the east wing, is in possession of about 65,000 book titles. Its editions up to 1900 alone number around 4,500 publications. According to the results of the recording of the publications of this specific period , which were published in 1989 (see in this regard, Giannis Karas, Τα ελληνικά έντυπα της Ι. Μ. Σίμωνος Πέτρας [The Greek Publications of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra]), the Library numbered 2,425 titles dating up to 1900. According to the above cataloguing, most of the editions are from the 19th century, with only 276 works dating back to previous centuries (17 editions from the 16th, 62 editions from the 17th and 197 editions from the 18th century). The oldest comes from 1513 – The Orations of Isocrates, Venice, from the printing house of Aldus Manutius. The library treasures not only books in Greek, but also in various other languages, such as French, English, German, Russian, Romanian, et al. In addition, over 40% of the books are encyclopaedias and works by Greek and Latin authors from the classical era onward.

, which were published in 1989 (see in this regard, Giannis Karas, Τα ελληνικά έντυπα της Ι. Μ. Σίμωνος Πέτρας [The Greek Publications of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra]), the Library numbered 2,425 titles dating up to 1900. According to the above cataloguing, most of the editions are from the 19th century, with only 276 works dating back to previous centuries (17 editions from the 16th, 62 editions from the 17th and 197 editions from the 18th century). The oldest comes from 1513 – The Orations of Isocrates, Venice, from the printing house of Aldus Manutius. The library treasures not only books in Greek, but also in various other languages, such as French, English, German, Russian, Romanian, et al. In addition, over 40% of the books are encyclopaedias and works by Greek and Latin authors from the classical era onward.

It should be noted that, throughout its run (that is, both before and after 1891), the Library of the Monastery maintained an open and functional character, lending books to its monks and to students attending the Athonite Academy.

The Archive of Simonopetra. In addition to the Library, the Monastery is in possession of an archive rich with material from the post-Byzantine period — mainly the second half of the 19th century — consisting of a number of Greek, Turkish and Romanian documents. The Archive has been documented and digitised.

Professor of history Antonis Liakos, who visited the Monastery in October 1990, pointed out that the Archive consisted of the following sections: the collection of Greek documents (patriarchal miscellanea, border and real estate documentation, information on metochia) from 1516 to 1800, the collection of Romanian documents (1433 to the 19th century), the collection of Turkish documents (16th – 20th century), the archive of documents from the 1800s to the present, and the settlements. The first two sections include most of the Monastery’s archival material.

The Archive’s documents include recordings of significant historical events, such as the revolution of 1821, the Crimean War, the Ottoman reforms and the establishment of the Romanian state. Furthermore, the Monastery’s archival evidence, such as its letters to the rulers of Wallachia, the patriarchal sigils and the letters to schools and associations of the hellenic community during its enslavement, provide valuable information about the orthodox world of the Balkans at the time, with Mount Athos serving as its epicentre. The total number of documents should be estimated at around 25,000 for the period between 1800 and 1900, and at a total of 40,000–45,000 if documents from 1900 onward are taken into account.

Furthermore, the Monastery’s archival evidence, such as its letters to the rulers of Wallachia, the patriarchal sigils and the letters to schools and associations of the hellenic community during its enslavement, provide valuable information about the orthodox world of the Balkans at the time, with Mount Athos serving as its epicentre. The total number of documents should be estimated at around 25,000 for the period between 1800 and 1900, and at a total of 40,000–45,000 if documents from 1900 onward are taken into account.

The settlements consist mainly of the Monastery’s accounts and receipts, which outline the infrastructures of commerce and the operation of businesses, especially in Smyrna and Constantinople, where it appears that the Monastery made frequent trades.

Library Organisation of Simonopetra. The Library is open to the public and can be visited on a daily basis. It is used by both scientists and students, as well as by pilgrims who spend time in the Monastery.

The books are categorised by subject matter and catalogued both in tabs and in an online index. The classification system used is the Dewey Decimal System, with appropriate adjustments made to accommodate monastery library data.

A section of the Library pertaining to the study of Mount Athos can be accessed from the Athos Library website with the option of reading and downloading all relevant articles and books in this field in pdf format. The same is true of the study of Meteora.

Publications of the Library of Simonopetra

The Monastery itself has published a series of: a) liturgical books, b) music books, c) volumes on Simonopetra, the lives of St. Simon, St. Magdalene, and the Monastery’s elders, as well as d) digital recordings of chants. In addition, in its capacity as a Library of Mount Athos, it has published a number of books on Mount Athos, the Monastery of Simonos Petra and various theological-ecclesiastical matters that are listed in detail on the Athos Library website.

Catalogues of the Library and Archive of Simonopetra

Vamvakas, D., “Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra. Catalogue of the archive”, Athonika Symmeikta, vol. 1, 1985, pp. 105–153.

Kadas, S., Notes on the manuscripts of Mount Athos. Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra, reprint from the Byzantina periodical #16 (1991), pp. 263–302.

Karas, G., The Greek publications of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra, Athens, IHR / NHRF, 1989.

Lambros, S., Catalogue of Greek codices in the libraries of Mount Athos, vol. Α’, Cantabria, England 1895, pp. 114–129.

Sotiroudis, P., Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra. Catalogue of Greek manuscripts, Mount Athos 2012.

Bibliography on the Library and Archive of Simonopetra

Liakos, A., Report on the Archive of Simonopetra, typewritten copy, 1990.

Pavlikyanov, C., "The structure of the Simonopetra Archive from 1809 to the mid-20th century", in Stojna Poromanska / Techni Grammatiki, pp. 111–149, Faber, 2005.

Simonopetra, Mount Athos, publishing director: S. Papadopoulos, ΕΤΒΑ Α.Ε., 1991.

- Chrysochoidis, K., “Greek documents” [Archive], Simonopetra, Mount Athos, pp. 263–267.

- Dimitriadis, V., “Turkish documents” [Archive], ibid., pp. 268–280.

- Nastase, D., “Romanian documents” [Archive], ibid., pp. 281–283.

- Markopoulos, A., “Inscriptions” [Archive], ibid., pp. 283–294.

- Chrysochoidis, K., “Manuscripts" [Library], ibid., pp. 295–299.

- Stathis, G., “Musical manuscripts” [Library], ibid., pp. 299–311.

- Karas, G., “Forms” [Library], ibid., pp. 311–313.

Sotiroudis, P., “Palaeographics from the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra”, Scientific Yearbook of the School of Philosophy of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Philological Faculty Issue #4, 1994, pp. 225–244.

Chrysochoidis, K., “Mount Athos. The Monastery of Simonos Petra”, Micro-photographs of manuscripts and documents, National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation, Historical and Palaeographical Archive, #2 (1978–1980), Athens 1981, pp. 24 & 47–49.

Chrysochoidis, K. / P., Gounaridis / D., Vamvakas, “Archive Catalogues: A. Holy Monastery of Karakallou, B. Holy Monastery of Simonos Petra", Athonika Symmeikta, vol. 1, Athens, IHR / NHRF, 1985, pp. 105–153.

Kapustin, A., Zamětki proklonnika Svajatoj Gory [Notes of a pilgrim of Mount Athos], Kyiv 1864, pp. 276–282.

Lambros, S., “Notes from Athens. Mss lost in the Burning of the Monastery of Simopetra”, The Athenaeum #98 (1.8.1991), pp. 161–162.

Nastase, D. / F., Marinescu, “Les Actes Roumains de Simonopetra (Mont Athos), Catalogue Sommaire” [Romanian documents of Simonopetra (Mount Athos), Brief Catalogue], Byzantine Symmeikta, vol. Ζ’, Athens, IHR / NHRF, 1987, pp. 275–418.